Editor’s note: This post is written by Martha Bless, an academic lead for ACUE, and Steve Mark, director of the Center for Teaching at Housatonic Community College.

How can you ensure that all faculty feel validated in their work with students? Supporting faculty in their teaching efforts is contingent on your ability to reach them.

We explored the challenge of scalability in faculty development last week at the POD Institute for New Faculty Developers in Saratoga Springs. In our session, we shared how ACUE and Housatonic Community College are training educators across campus as part of Connecticut’s statewide initiative to promote student success through effective instruction. As Housatonic’s campus facilitator, Steve talked about building a community of faculty learners using ACUE’s online Course in Effective Teaching Practices. As ACUE’s academic lead, Martha then showed session attendees how the course is designed to help all faculty learn and apply evidence-based teaching practices at scale.

We’ve summarized some of highlights from last week’s discussion below. How have you cultivated communities of practice? Tell us in the comments section!

Comprehensive and Evidence-Based

The program at Housatonic Community College consisted of faculty from a range of disciplines, from engineering to business to psychology. It gave many of them a chance to have meaningful conversations about teaching across rank and discipline, which is a key element of the Housatonic Center for Teaching’s philosophy. The course sparked great conversations that began in our online forums and continued in person. Sometimes, course takers would stop me in the hall to continue a particular discussion thread. Other times, they just wanted to share their enthusiasm about a teaching technique they had learned and the impact it had on their students.

This was possible because ACUE’s program addresses a core set of pedagogical skills and knowledge for all college educators—regardless of discipline. The course is fully aligned to ACUE’s Effective Practice Framework, which identifies and organizes these instructional practices. This was the result of a comprehensive literature review consisting of over 350 citations from the scholarship of teaching and learning and extensive consultation with subject matter experts. Throughout the course’s 25 modules, course takers see a diversity of subjects, disciplines, students, and faculty represented in the material. Again, the idea is to emphasize that evidence-based teaching is universally applicable.

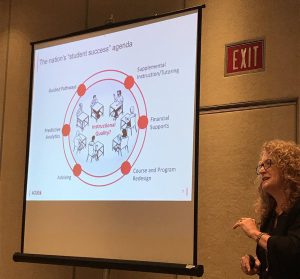

Improving teaching and learning needs to be on the student success agenda! #INFD17 pic.twitter.com/5sRsLZM7fF

— Chris Price (@chrisprice117) June 22, 2017

Cohorts Are Key

To help faculty developers and teaching center directors engage faculty at scale, ACUE’s course is built online. In every module, course takers can complete several components on their own, an intentional design element that takes into account varied and busy schedules.

But the research is clear that the best way for instructors to learn new teaching techniques is by engaging in focused learning conversations with other faculty. That’s why the course is designed for cohorts of faculty, in which course takers deepen their learning through a series of advanced interactive exercises in each module. In Observe and Analyze, faculty watch videos of teaching practices demonstrated in a developing way, and then analyze which of the instructional techniques are used effectively and which are developing and why. These online discussions give course takers the ability to share and discuss their thoughts on the possible adjustments with their cohort and a facilitator. These discussions are great launching points for instructors to move into the final section, Practice and Reflect, which we describe in more detail below.

| Sign up for The Q Newsletter for weekly news and insights. |

The initial Housatonic cohort included new and veteran faculty as well as adjuncts. The cohort experience began with a face-to-face orientation to the course, at which faculty had a chance to meet fellow cohort members, share their teaching goals, and begin to build relationships with colleagues they may not have known before. That kickoff event enhanced the online collaboration because faculty could connect names and faces in the online discussions. After the orientation, the Housatonic faculty learners completed two ACUE modules per week throughout the semester. They participated in lively discussions, posted their analyses of teaching practice in the Observe and Analyze sections, and shared their own teaching ideas and experiences, all of which helped to strengthen a faculty-led learning community of practice at Housatonic.

Facilitators: Experts, Coaches, Cheerleaders

Facilitators are critical to cultivating a community of practice. These are expert educators who can effectively help moderate conversations, facilitate group discussions, and provide one-on-one coaching to keep course takers motivated and engaged. Facilitators guide faculty through the course, monitor course takers’ progress and cheer faculty on by celebrating successes and highlighting key points in the online discussions, and serve as mentors and coaches by providing insights about teaching techniques. This keeps the cohorts working together as they progress through the course.

As director of Housatonic’s Center for Teaching, Steve is a natural fit to be the facilitator, and he serves many roles. As a coach, Steve works individually with course takers online and in person to help them navigate the course and develop their postings. As an expert in facilitating discussions, he knows how to get the conversation going, draw in more participants with a well-placed prompt, and jump in to bring clarity and focus to the subject. Throughout, he posts announcements, reminders, and shout-outs to keep the cohort engaged and on track.

Application: Practice & Reflect

To complete each module and earn a badge endorsed by the American Council on Education, course takers are required to apply teaching techniques they have learned from the course, and then write rubric-aligned reflections about what went well, the challenges they encountered, and their next steps for continuing to refine their practice. As part of this process, course takers receive feedback on their reflections from the colleagues in their cohort and their facilitator. They also review their colleagues’ reflections to hear about their experiences and share useful resources.

Faculty in the Housatonic cohort reported that writing and sharing reflections on their teaching practice and reading those of their colleagues had a positive effect on their instruction. Veteran faculty said it helped them to be more intentional about their teaching and that it reinvigorated their enthusiasm for teaching. It caused them to rethink some of the techniques they had been using, implement new techniques, and, in some cases, resume techniques they had used in the past but had since forgotten or replaced with other predictable—but less engaging—techniques. New and adjunct faculty, many of whom had little or no previous preparation in effective teaching practices, remarked on how helpful the course and reflective practice was for them as new full-time instructors or professionals who teach part time. The community of practice created through the cohort experience also made them feel like welcome and valued members of the Housatonic community at large. Finally, as facilitator, Steve also benefited from the reflective practice, because reading the faculty reflections gave him insight and areas of focus for programming for his role as director of the Center for Teaching at Housatonic.

How do you support faculty in their teaching efforts on your campus? Let us know in the comments section!