New Resource for Inclusive and Equitable Teaching

As educators, we must work to create welcome and inclusive learning environments that promote equitable and successful outcomes for every student. We also know that learning is more than an intellectual exercise. Students bring to our classes their hopes for the future, their fears of failure, and the range of emotions one experiences when encountering […]

Innovative Teaching for Success at CUNY

“We call ourselves the American Dream Machine,” Dr. Félix V. Matos Rodríguez, chancellor of the City University of New York (CUNY) said in the October 2, 2020 “Conversation on Student Success” part of the series produced by ACUE and the American Council on Education (ACE). Sherri Hughes, assistant vice president of professional learning at ACE, […]

Webinar Recap: Examining and Mitigating Implicit Bias

“As human beings, we’re not fond of ambiguity,” said Theresa Nance, PhD, vice president for diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer at Villanova University, as she opened a mid-October conversation on Examining and Mitigating Implicit Bias, the latest in ACUE’s series of Inclusive Online Teaching webinars. “We fill in gaps with our knowledge and our […]

New Resource for Inclusive and Equitable Teaching

Faculty Resources for Uncertain Times

Our college and university classrooms, online and in-person, have long been spaces for civil discourse and the expressions of emotions, perspectives, hopes and fears. A presidential election year often introduces additional feelings, including uncertainty, among many students. To support faculty in creating supportive and inclusive learning environments—including facilitating challenging conversations and practicing self care, we’ve […]

Preparing an Inclusive Online Course: Webinar Recap

“It’s even more important right now to ensure we’re creating courses that are inclusive,” Farrah Ward opined in the webinar Preparing an Inclusive Online Course, the second webinar in ACUE’s Inclusive Online Teaching webinar series, presented in collaboration with the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU), the American Council on Education (ACE), the […]

Resources for Inclusive Online Teaching

Learn how to prepare an inclusive online course

Small Courses, Big Impact at CU Denver

University of Colorado Denver partners with ACUE to scale teaching excellence through microcredential courses At every university, there are pivotal courses that can “make or break” a student’s collegiate career. The University of Colorado Denver (CU Denver) refers to courses that have the largest impact on student success and retention as “influential courses,” and leadership is committed […]

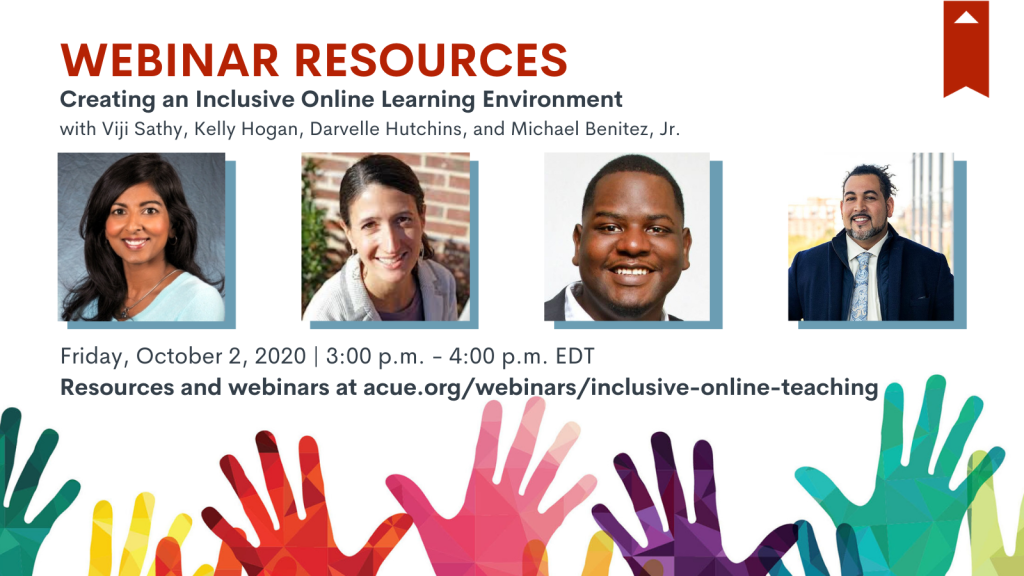

Creating an Inclusive Online Learning Environment: Webinar Recap

“How do we continue to rupture practices that are grounded in convention to teach with equitable outcomes?” Dr. Michael Benitez, Jr., vice president for the Office of Diversity and Inclusion, Metropolitan State University, Denver, asked in Creating an Inclusive Online Learning Environment, the first in ACUE’s series of Inclusive Online Teaching Webinars. This webinar was […]