By R. Eric Landrum

I have never met a faculty member in my 30-year career who took the summer “off.” Even when an instructor has a nine-month contract, in my experience, most use the time to catch up on their field’s literature, conduct research, connect with colleagues, write, and strengthen their teaching. It’s who we are.

I have never met a faculty member in my 30-year career who took the summer “off.” Even when an instructor has a nine-month contract, in my experience, most use the time to catch up on their field’s literature, conduct research, connect with colleagues, write, and strengthen their teaching. It’s who we are.

Over a break, I believe the “three Rs” are vital for continued and sustained success in teaching: reflecting, recharging, and readying.

Reflecting

The educational and cognitive value of self-reflection is well established in an existing and growing literature that has identified principles that apply widely—to students reflecting about assignment and exam performance (e.g., Lester, 2019; Nilson, 2013), faculty members reflecting on a particular class session (e.g., Gross Davis, 1993), and, in the present case, an educator reflecting on an entire semester, quarter, or term. It is a form of metacognition, with an individual comparing an outcome or their performance against a goal or standard and then assessing their affective feelings about that self-judgment (Silver, 2013), such as when an educator “takes stock” of her or his teaching effectiveness.

Increasingly, faculty members perform what I would call micro-reflections: a written assessment, such as in a teaching journal, immediately after the completion of a particular exercise, assignment, or class session, For example, last fall I made notes about an assignment in my upper-level capstone class right after I finished grading 70 capstone student assignments. Ideas for improving the assignment were fresh on my mind. When I went to update and post that assignment this spring, I was pleasantly surprised by the notes. Like a letter mailed to myself, they included ways to improve the assignment instructions and the grading rubric.

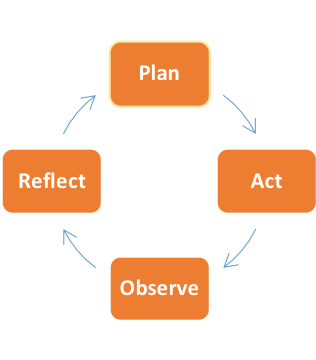

Alongside these micro-level reflections are a type of “macro-reflection” developed in the action research literature (e.g., Holly, Arhar, & Kasten, 2009; Riel, 2011), as depicted by the graphic here. I consider these macro-reflections a self-assessment of one’s teaching over the first portion of a break between terms, to reflect about the previous semester or academic year.

What should macro-reflection entail? It should:

• Contain positive observations as well as suggestions for improvement

• Include your short view of teaching (e.g., day-to-day challenges to address through particular techniques) and your long view of teaching (e.g., major areas to refine in the coming years)

• Take into account where you are in your career path

• Be shared with a trusted mentor for candid feedback

• Contain goal statements for the future, like good learning objectives, that are clear, specific, actionable, and observable.

Recharging

I believe this type of macro-reflection is best done over an extended period of time, such as a summer break, and in combination with a recharging phase, when you can step away from your chief responsibilities of being an educator. You may not be able avoid all duties, may need the income from teaching a summer session, and may keep checking emails from time to time. But stepping away from the intensity of teaching creates the necessary space and perspective for quiet and deep reflection—and to avoid burnout.

Burnout is typically defined along three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (i.e., feelings of being depleted of emotional and physical resources; not able to give more of oneself), cynicism or depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment (i.e., inefficiency, the loss of professional sense, the tendency to evaluate negatively) (Garcia-Arroyo & Osca, 2017; Padilla & Thompson, 2015). The World Health Organization has recently redefined burnout as a chronic stressor at work (Chatterjee & Wroth, 2019). Burnout is classified as an occupational phenomenon rather than a medical condition.

If you feel like you are slipping into burnout, you can take steps to recover and recharge. In a survey of faculty from U.S. doctoral-grading research universities, Padilla and Thompson (2015) reported four statistically significant predictors related to reducing burnout:

• more social support

• more hours spent with family

• more hours spent on leisure activities

• more hours spent sleeping.

This might mean catching up on that stack of pleasure reading you’ve been meaning to enjoy. It might mean taking that trip to see family members or former college roommates like you’ve been promising to do for years. Remember that hobby you used to do when you were younger that you enjoyed so much? Why not take a little time in the summer to pursue that creative hobby, visit that local winery, or re-make those flower beds in the front yard? Odds are, when you next teach, you’ll find it more rewarding.

Readying

With the benefits of some recharging, it’s time to start to ready yourself for the next semester and avoid a rough re-entry. I made the mistake once of not making sufficient preparations for my next term—my syllabi weren’t updated like I wanted them to be, and my LMS course sites weren’t up and running on the first day of class like I prefer. I was just plain behind, and it caused avoidable stress for me and my students.

This is when your end-of-term macro-reflection becomes so useful. Rather than planning in the usual way, the adjustments you make in the weeks and days before new term, and continue to make during the term, should be informed by the observations you made when semester had just ended, the feedback from a trusted peer, and the goals you set. ACUE provides numerous resources to support this planning through its Community of Professional Practice, and ACUE-credentialed faculty members have continued access to course resources that are evidence-based and helpful. Your disciplinary association and teaching center may also provide teaching resources.

The bottom line, moral of the story is this: invest in yourself. Taking some time to reflect on what just happened is a good investment. Recharging, getting away from the grind, inoculating yourself against burnout and fatigue is a good investment in you and your future professional happiness. Planning the time to re-enter the rhythms and the flow of the semester, informed by your own reflection, is a welcome benefit.

References

Chatterjee, R., & Wroth, C. (2019, May 28). WHO redefines burnout as a ‘syndrome’ linked to chronic stress at work. NPR. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/05/28/727637944/who-redefines-burnout-as-a-syndrome-linked-to-chronic-stress-at-work

Garcia-Arroyo, J. A., & Osca, A. (2017). Coping with burnout: Analysis of linear, non-linear and interaction relationships. Anales de Psicologia, 33, 722-731. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.279441

Gross Davis, B. (1993). Tools for teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Holly, M. L., Arhar, J. M., & Kasten, W. C. (2009). Action research for teachers: Traveling the yellow brick road (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson.

Lester, K. F. (2019, April 23). Multiple modes of reflection. Association of College and University Educators. Retrieved from https://community.acue.org/blog/multiple-modes-of-reflection/

Nilson, L. B. (2013). Creating self-regulated learners: Strategies to strengthen students’ self-awareness and learning skills. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Padilla, M. A., & Thompson, J. N. (2015). Burning out faculty at doctoral research universities. Stress and Health, 32, 551-558. doi:10.1002/smi.2661

Riel, M. (2011). Understanding action research. Center for Collaborative Action Research, Pepperdine University. Retrieved from http://cadres.pepperdine.edu/ccar/define.html

Silver, N. (2013). Reflective pedagogies and the metacognitive turn in college teaching. In M. Kaplan, N. Silver, D. Lavaque-Manty, & D. Meizlish (Eds.), Using reflection and metacognition to improve student learning (pp. 1-17) [In J. Rhem & S. Slesinger (Series Ed.), New pedagogies and practices for teaching in higher education]. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Eric Landrum is a professor in the Department of Psychological Science at Boise State University in Boise, ID. He received his PhD in cognitive psychology from Southern Illinois University-Carbondale, and his research addresses the improvement of teaching and learning using SoTL strategies as a scientist-educator.

Nationwide, the guided pathways movement is helping more students succeed. But as Sova co-founders Alison Kadlec and Paul Markham observe, “not nearly enough has been done to meet faculty where they are, speak to their interests, and bring them into this work as true partners.”

Nationwide, the guided pathways movement is helping more students succeed. But as Sova co-founders Alison Kadlec and Paul Markham observe, “not nearly enough has been done to meet faculty where they are, speak to their interests, and bring them into this work as true partners.”