Fostering Collaborative Learning by Using the Jigsaw Technique

By Youn Jung Huh

Working in groups is considered an important skill in almost every job field, and students should acquire this skill before they graduate from college. In the beginning of my education classes, I always do a quick survey to gauge students’ previous learning experiences and their personal learning styles. Many of my students often mention that they prefer to work in groups, yet they also report that group projects are one of their most challenging assignments. This means that even if they like to work with others, they may not know how to collaborate to achieve the same goal. To support students who are not equipped with the skills to do collaborative work, I applied some of the techniques discussed in ACUE’s Course in Effective Teaching Practices, including the Jigsaw technique, facilitating in-class group workshops, and running debriefing sessions after each group workshop.

Jigsaw as a way to prepare students to work in groups

I implemented the Jigsaw technique to help students acquire skills to work as a group, as discussed in ACUE’s module “Using Active Learning Techniques in Small Groups.” Below are the steps that I followed:

1. Divide the lesson into segments.

2. Assign segments to different groups. Each group becomes the expert in one segment.

3. Each group prepares to teach a lesson on their segment to the class.

4. Each group teaches their segment. Other students listen and ask questions.

I asked students to make a list of significant issues in the education field, and then to choose one to research. Based on their interests and the course objectives, I was able to arrange five research teams that focused on different issues. For this research project, individual students were responsible for contributing their study results to the group’s final presentation, as well as participating in the in-class group meetings, collecting and analyzing data, and preparing materials for the presentation.

While students worked in groups for their research project, I checked to make sure each group understood their part of the project by asking questions and providing additional materials. I also carefully observed the individual students. This information helped me to determine how to facilitate the next group meeting and assign roles to individual team members.

| What to read next: Three Misconceptions About Using Active Learning in STEM |

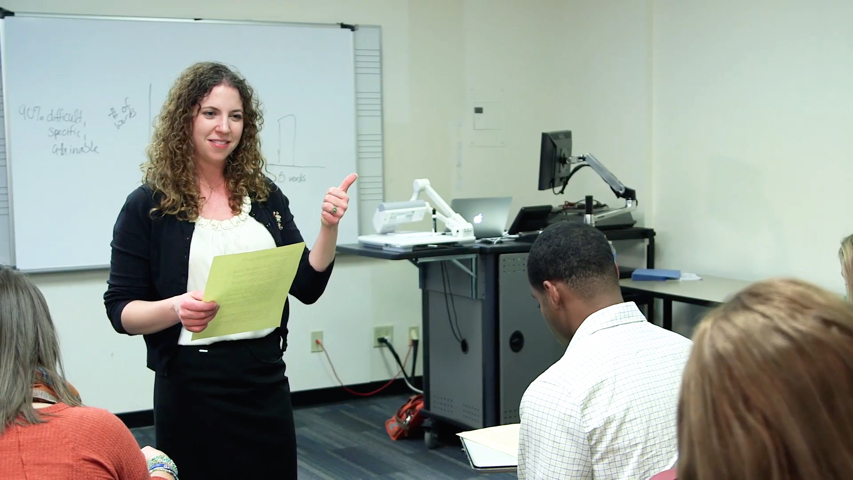

In-class group workshop

I provided three in-class group workshops to students to develop their shared expectations, set goals as a group, and develop a habit of working in groups. In each workshop, I explained their goal for the meeting and provided a guideline, which included a to-do list and timeline of the project. Additionally, in the first group workshop, I asked each group to select one leader and one recorder to more effectively communicate with the group members and monitor the group projects.

The in-class group workshops enhanced the Jigsaw technique, as I could respond to students’ immediate needs and monitor how they chose their research topic, specified research questions, and found ways to answer the research questions.

|

Suggestions for implementation: • Start the class by sharing an overview of or agenda for the workshop. • Provide a rubric that explains how students’ work will be evaluated individually and as a group. • Break down the session into small steps with time frames so students can stay focused on their work and accomplish their goals in the allotted time. • Monitor each group’s progress by asking questions and taking notes. Read the group dynamic. There will likely be someone who appears to be struggling to be part of the group. |

Debriefing session

At the end of each in-class group meeting, I had a debriefing session with each group. For the debriefing session, the recorders needed to write a brief summation of the meeting minutes, describing their progress and their individual plan for the next meeting. The group leaders also reported the group’s work to get my feedback at the end of the meeting. During this time, we were able to identify what needed to be done and roles for each member of the project. This helped students stay on task and be aware of their roles on the team. Also, it helped me identify students who did not actively participate in the group meeting and find ways to support them. I met with these students individually after class or during my office hours to guide them toward doing their part of the research project.

|

Suggestions for implementation: • Provide a skeletal outline. This will be used as the form for meeting minutes and as a checklist of tasks to accomplish within a given time frame. • Make the debriefing session a conversation rather than a one-way report from the group leader to the instructor. Give students time to ask questions and encourage them to reflect on and address their contributions to the project. |

Without a thorough plan and systemic guidance, we cannot simply expect students to acquire skills for collaborative work. Students need to develop a habit of working as an active group member through meaningful learning experiences in class. Setting aside regularly scheduled group work time in class is not easy since we have topics we must “cover” in each class, but it will help the students develop a skill set for collaborative learning, and most importantly, as explained in ACUE’s course, it will “help students improve their foundational knowledge, higher order thinking, and social skills.”

Youn Jung Huh is an assistant professor in the school of education at Salem State University. Her research interests include early childhood education, young children and digital technology, and teacher education. Her most recent publication is titled “Uncovering young children’s transformative digital game play through the exploration of three-year-old children’s cases,” published in Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. She earned her ACUE credential in spring 2018.

| What to read next: Using Active Learning Techniques in Small Groups |

News Roundup: Student Agency

This week, promoting student agency and curiosity and encouraging students to be vulnerable.

| Sign up for The ‘Q’ Newsletter for the latest news and insights about higher education teaching and learning. |

Tech, Agency, Voice (On Not Teaching)

Rather than establishing a hierarchy with students at the bottom and dispensing information, Chris Friend urges instructors to encourage students to discover and create. For instance, in his introductory writing and rhetoric courses, Friend poses questions about writing and technology and asks students to research the answers, giving them the opportunity to explore independently and ignite their own curiosity. (Hybrid Pedagogy)

Resiliency in Science: We Need to Stop Punishing Vulnerability

“Vulnerability is not a weakness in science,” Jonathan Thon writes. He urges science instructors to undergo empathy training to learn how to help students persevere in the face of obstacles and be mentors to the students they teach. (University Affairs)

A Third of Your Freshmen Disappear. How Can You Keep Them?

When the retention rate decreased at Southern University of Utah, the university overhauled its first-year experience program. Changes included redesigning the first-year seminar and identifying struggling students earlier; as a result, Southern Utah saw a notable rise in retention. This approach reflects a nationwide trend to use multiple solutions to promote student success. (The Chronicle of Higher Education – Paywall)

From Status Quo to Status Go: Scaling Innovation in Higher Ed

Innovation needs to take place on an institutional level in order for it to succeed, Vincent Del Casino, Jr., opines. For example, after the recession, the University of Arizona worked to embrace change by putting entire programs online, incentivizing faculty to redevelop their courses in a virtual environment. (The Evolllution)

Gamification in Education

According to Pooja Adarkar, the principles involved in gamification are applicable to many fields and can motivate and engage students. Some methods for using gamification in education include using a points system, so students must complete certain assignments to advance to a new “level,” and awarding badges for completed assignments. (The Faculty Center Blog—Pace University)

Partner News

Sam Houston State University: SHSU ACUE Fellows complete the Course on Effective Teaching Practices, endorsed by ACE (American Council on Education) (Sam Houston State University)

University of Southern Mississippi: ACUE Institute Program Popular Resource with Southern Miss Faculty (Southern Miss Now)

We must give our students stability.

Teaching Through Change

By Aubree Evans

Years ago, I taught writing courses at a university in a Gulf Arab country. My students were young women with stressful lives. Many of them were starting to think about whether their futures would involve travel, more education, or marriage. The students I taught had grown up in a burgeoning Westernized city in which 88% of the population was made up of expatriates. People from all over the world would come to work for two- to five-year contracts. To illustrate the weight of this phenomenon, there was a space-themed amusement park in this city that had been abandoned because the company’s contract ended. Roller coasters and buildings that looked like planets were simply neglected in the sand.

Years ago, I taught writing courses at a university in a Gulf Arab country. My students were young women with stressful lives. Many of them were starting to think about whether their futures would involve travel, more education, or marriage. The students I taught had grown up in a burgeoning Westernized city in which 88% of the population was made up of expatriates. People from all over the world would come to work for two- to five-year contracts. To illustrate the weight of this phenomenon, there was a space-themed amusement park in this city that had been abandoned because the company’s contract ended. Roller coasters and buildings that looked like planets were simply neglected in the sand.

Every time a teacher or principal of a school would leave at the end of his or her contract, these students would suffer. Change, to them, was felt as starts and stops in curricula, abandoned textbooks, and unfinished projects. When one person left, a new one came in and did things differently. Another element in this ever-changing environment was that the government in this country is that of a top-down Islamic dictatorship. This means that when the sheikh changes a policy or appoints a new leader, everyone accepts it and adapts.

In order to connect with my students and warm up their writing muscles, I always asked them to write in their journals for the first 10 minutes of each class meeting. For 10 minutes twice a week, they could share anything they wanted. Later I read their entries and made comments only on content, never mechanics. I also promised that whatever they shared stayed only between us. My outsider status made me a fairly safe confidante since I didn’t know anyone in their social networks.

Journal entries that stand out in my memory include whether or not to get one’s hair cut into “fringe” (aka bangs), spending time with family at the beach, feeling tired and stressed, being hungry (I started carrying snacks), and family illness. One young woman, Mariam, whose name I’ve changed to protect her identity, wrote about the progress of her mother’s cancer. The first entry at the beginning of the fall semester described the shock of her diagnosis. In each entry, the diagnoses and symptoms worsened. Through this, 17-year-old Mariam had to take care of her siblings as well as her mother. As I read each of her entries, I would write comments to be as comforting as possible like “You are so strong for your family!” or “I am so sorry you’re going through this, Mariam.” She never wrote about any other topic during journal time. Each entry was about her mother’s illness.

This semester there were major administrative changes at the university. A new president, new provost, and new department chair led to many new policies. As a result, I received pressure to stop the “extra” things I was doing in my classes like journal writing and book reports. Around mid-October, I stopped the journal-writing time and taught only required course content. I deeply missed the intimate communication with my students, but I was shaken by the changes and in survival mode.

At the end of the semester, which was mid-January there, the final exam was to write an essay. At the end of a long day of administering exams, I took my stack of essays to a local restaurant to grade them. To help increase objectivity, I try not to look at the name on a paper before I grade it. About 15 minutes into the grading session, I started reading an essay about the death of the writer’s mother. I flipped the paper over and saw Mariam’s name at the top. I felt sick as I realized that three months had passed since I had read about her mother’s progress with cancer. That was the last time I had asked her to write a journal entry and given her time and space to share herself with me. In those three months, her mother had died, leaving this young woman to pick up the pieces and take care of her family. At the same time, she was working extremely hard in my class, and she never said a word about her life circumstances or complained in any way.

As I sat in this public restaurant booth sobbing loudly over this essay, I knew that I had failed my student. I had allowed changes external to the class affect what should be the still and constant space inside the classroom. If I could do it over again, I would have tried harder to continue the journals. At the very least, I should have asked my student about her mother. In a world rife with change, we can we must find small ways to give our students stability, whether it’s through keeping an established routine or simply continuing a conversation that we’ve begun.

Aubree Evans is the coordinator for teaching, learning, and academic excellence in the Center for Faculty Excellence at Texas Woman’s University. Her research interests are the sociology of higher education, authentic assessment, and power in the classroom. She facilitated ACUE’s program at TWU in 2017–2018.

News Roundup: How to Engage Students

This week, instructors and teaching experts discuss practices for engaging students in a course.

| News and insights delivered to your inbox every week: The ‘Q’ Newsletter. |

How One Teaching Expert Activates Students’ Curiosity

In her workshop, “The Power of the ‘Naïve Task,’” Kimberly Van Orman explores how instructors can encourage their students to think critically about course material using only preexisting knowledge. In her method, students work together to solve puzzles or dilemmas, in the process challenging one another and becoming curious about the subject. (The Chronicle of Higher Education Teaching Newsletter)

Why Do So Many Students Drop Out of College? And What Can Be Done About It?

Considering the large percentage of students who drop out of college, Jeffrey Selingo urges instructors and colleges to promote the success of all students. He uses the example of David Laude, who changed his teaching approach by putting at-risk students in smaller classes. (The Washington Post)

Freshmen ‘Are Souls That Want to Be Awakened’

On the first day of class, Bryan Dewsbury asks students to shoot baskets into the trash can at the front of the room from their seats. This is meant to demonstrate that students are all starting from different places. Dewsbury also meets with students one-on-one at the beginning of the year and takes other measures to ensure that his teaching is inclusive. (The Chronicle of Higher Education)

The Spark of Learning

In her book The Spark of Learning, Sarah Rose Cavanagh suggests considering students’ learning an element of their emotions. Engaging in mindfulness and beginning a course with a short mystery or puzzle are two noteworthy strategies Bonni Stachowiak recommends from the book. (Teaching in Higher Ed)

3 things to do now to benefit students this fall

Ensure a Strong Semester With These Strategies

The time between semesters is an opportunity to reflect. How have we been successful during the past semester? Where might we make some adjustments to our courses? Although we may not feel the need to do a full course redesign, even small changes to our teaching can have a significant impact on students’ learning experiences. Here are three practices you might consider implementing to ensure a strong start, paired with quick reads from some of our teaching and learning experts:

1. Use feedback from this semester’s students to inform adjustments to your instructional practices. Consider the responses you received most frequently from students in any solicited feedback—anonymous surveys, Stop-Start-Continue exercise, point-of-view postcards, your institution’s course evaluations, etc.—and informal feedback from speaking with students before/after class and during office hours. Compile a list of patterns in students’ responses, and then prioritize them based on which adjustments can be made and which will have the greatest impact on students’ learning. Additionally, if you kept a journal this semester, look over your notes from each class session to see what changes you might make based on your observations. Both mid- and end-of-semester feedback can be used to guide adjustments given the process of collecting and acting on feedback is similar (i.e., solicit feedback from students, identify common responses, make adjustments, and tell students why you are making or have made certain changes); that’s why our recommended reads include posts on midsemester feedback.

Recommended reads:

• José Bowen: “Using Feedback From Students to Improve Your Teaching”

• Viji Sathy: “The Sweet Spot of Midsemester Feedback”

• Penny MacCormack: “A Metacognitive Approach to Midsemester Feedback”

2. Revise one assignment to make expectations more transparent for students. According to Mary-Ann Winkelmes of the Transparency in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education project (TILT), focusing on the purpose, task, and criteria of assignments “promotes an inclusive learning environment where teachers and students engage in conversations about the relevance of academic work to students’ lives beyond college, as well as expectations for work process and performance.” By making assignments more transparent, students benefit from clearer instructions and from understanding the relevance of course tasks, and you save time assessing their performance. Winkelmes suggests starting small by revising one or two assignments. You can use the transparent assignment template as a guide, and read Winkelmes’s article below to learn more.

Recommended read: Mary-Ann Winkelmes: “Small Teaching Changes, Big Learning Benefits”

3. Prepare a syllabus that gets students excited about learning. As a supplement to your traditional syllabus, consider developing a graphic syllabus as a visual depiction of the relationships between course topics. Linda Nilson states that a graphic syllabus benefits students because “they get an overall big picture of the field, a big picture of the course. Their minds photograph it, so they have a general idea of the shape, the flow, and they follow it like a map. It helps students remember because it gives students a structure for their knowledge.” Alternatively, you might create a big ideas syllabus that lists the major concepts that guide your course and that you want students to remember, with the key assignments and activities aligned to each idea noted underneath. Michael Wesch recommends that you “go back to each of your lectures, for example, and think about ‘What is the actual big idea? What is the change I’m trying to create in my students through this lecture?’ Once you figure that out, you can reimagine everything else, like is that content you’ve been covering necessary for that idea or is there better content?” Resources like a graphic syllabus or big ideas syllabus can increase students’ engagement in your content and their motivation to learn. For inspiration on syllabus redesign, see our recommended read.

Recommended read: Michael Wesch: “What Inspired Me to Redesign My Syllabus”

For more teaching and learning resources, visit our community.

The Quizemption: When Opting Out Is a Positive Choice

By Juanita M. Eagleson

The tension is palpable. The air is rife with nervous energy, and anxiety is now a living organism. The men and women, the teenagers, the seniors, they all come to realize there is only one way out for them—back through the classroom door. Those who were quick enough to grab the front row seats would have the best chance of making a clean break for the exit. The less aggressive would likely be trampled as they fought their way to freedom. The aftermath—unimaginable. It would be pure carnage once again. Why, oh, why?! The simple answer: to escape the dreaded QUIZ!

The tension is palpable. The air is rife with nervous energy, and anxiety is now a living organism. The men and women, the teenagers, the seniors, they all come to realize there is only one way out for them—back through the classroom door. Those who were quick enough to grab the front row seats would have the best chance of making a clean break for the exit. The less aggressive would likely be trampled as they fought their way to freedom. The aftermath—unimaginable. It would be pure carnage once again. Why, oh, why?! The simple answer: to escape the dreaded QUIZ!

Drama? Maybe not so much, but certainly general anticipation on the part of my students that something foreboding was on the horizon with a questionable outcome. For English Composition II at the University of the District of Columbia Community College, the culmination of the course is the academic argument (research) paper. Because there is a very deliberate process to constructing the paper, I administer short quizzes along the way to assess the students’ progress in understanding the elements of argument. There are typically six or seven quizzes per term, no more than 10 minutes in length, that are scheduled for the beginning of every other week.

As it turned out on this not-so-typical day near the beginning of the term, the quiz was supposed to be about ethos, pathos, and logos. I heard some groaning, as well as a few words of encouragement exchanged between two students sitting side by side. “I got this covered,” one student said. “I studied my notes from Martin Luther King’s Birmingham Letter,” the other responded. I chimed in with a few words of reassurance. “I’m sure you’ve all reviewed your notes and will do well.” At that point, I had planned to hand out the quiz.

On this occasion, however, a courageous student sitting in the back of the classroom raised his hand and said, “I’m not really prepared for this quiz.” I almost dismissed his comment but then realized that there were a few other students nodding their heads in agreement. So, I asked them why they were not prepared. The answers essentially boiled down to “I didn’t really have a chance to study.” Many of my students face daily challenges, family responsibilities, and personal obligations that encroach on what would ideally be considered study time. For the most part, their responses were not excuses; they were circumstances.

At that moment, I recalled a comment from one of the instructors in the ACUE module on “Developing Self-Directed Learners”: that faculty should enable students to make decisions as learners. I took that to also mean that students should have the opportunity to weigh in on the quiz process and take responsibility for being prepared. I saw this as a chance to gather feedback about how they prepared for quizzes. After some discussion, I decided to abort the quiz, review the material, clarify any confusion about the topic, and, finally, allow an additional week for them to prepare for ethos, pathos, and logos. While being fully transparent about the content of the quiz, even having them construct several of the questions, I wasn’t satisfied that this addressed the issue of future quizzes and the underlying objective of developing self-directed learners.

After scanning the resources provided in the ACUE module, I took a second look at the “Amnesty Coupon” and read what it was meant to do—that is, “to offer students flexibility with assignment and exam dates.” With that in mind, I explained to the class that they would each get one “quiz amnesty coupon” as an exemption to be used on the day for any quiz of their choice. Eyes glowed. Smiles bloomed. Being in control of this aspect of their class experience was a welcome bonus for them.

One student was quick to point out, however, that she had an instructor who dropped the students’ lowest grades. She wanted to know if using the coupon was the same. I explained that although both actions had an impact on the grade, by using the coupon, the result would be immediate. Moreover, the decision not to take the quiz was under the control of the student. For those who used the coupon, I calculated an average of the quizzes taken for the term. For those who didn’t use the coupon, I dropped the lowest grade.

I expected a rush of students gleefully and immediately handing in quiz coupons, but to my amazement only two students actually took the option of not taking a quiz over the 16-week course. I have only used the amnesty coupons for one term, but I look forward to using the “quizemption” next term and, perhaps, seeing fewer students running for the exit.

Juanita M. Eagleson is an assistant professor of English at the University of the District of Columbia Community College in Washington, DC. Her latest research includes the impact of ageism on student learning and faculty teaching effectiveness. She completed ACUE’s program in fall 2017.

News Roundup: Metaphors for Teaching

This week, instructors explore how classics, podcasts, and other media and art can inform and mirror the teaching process.

| Sign up for The ‘Q’ Newsletter for weekly news and insights. |

Where Do We Wish to Go in Higher Education?

Using Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Wife of Bath as a metaphor for finding a consensus on an appropriate direction for higher education, Jessica Riddell offers her own suggestions for how to approach the issue, such as listening to students’ voices and perspectives and trying new instructional methods in the classroom. (University Affairs)

Do Photos of Teaching on Your Campus Look Staged and Static?

Wanting to share examples of inventive teaching to start a discussion about instruction, Cassandra Volpe Horii collaborated with Martin Springborg to create a photography exhibit of teaching and learning at Caltech. Horii hopes the exhibit will inspire instructors to try new styles of teaching. (Vitae)

The Pedagogy of Podcasts

Kristi Kaeppel and Emma Bjorngard-Basayne explain how faculty can make their content more engaging by applying lessons learned from podcasts. For example, podcasts use storytelling to bring content alive, make material relevant, and break down concepts—strategies that can be used in the classroom as well. (UConn)

Smartphones in the Classroom

Many students mistakenly believe that their classmates use technology for personal reasons during class, according to a new study, which could lead more students to go off task. C. Kevin Synnott urges instructors to share this misconception with students to initiate a discussion about using technology for educational purposes. (University Business)

What 6 Colleges Learned About Improving Their Online Courses

Researchers from Arizona State University and the Boston Consulting Group found that online education can boost retention and graduation rates, but instructors need to develop a range of delivery methods to meet students’ needs. For instance, at some schools, instructors use technology to give students personalized feedback. (EdPlus)

Partner News

California State University System: CSU and California Community Colleges Partner on a Tool to Find Transferable Online Courses (EdSurge)

Miami Dade College: Report: Americans are finding work, but the better-paying jobs require a college degree (Miami Herald)