Q&A with Michael McPherson

Editor’s note: Last week, we sat down with Michael McPherson, co-chair of the Commission on the Future of Undergraduate Education, for an insightful discussion about why colleges and universities should invest in their faculty, measure the impact of good teaching, and create more productive working environments specifically for their adjunct faculty members. McPherson highlighted some of the important findings published last fall in The Future of Undergraduate Education, The Future of America.

1. Why should institutions invest in quality instruction when they have so many competing priorities?

1. Why should institutions invest in quality instruction when they have so many competing priorities?

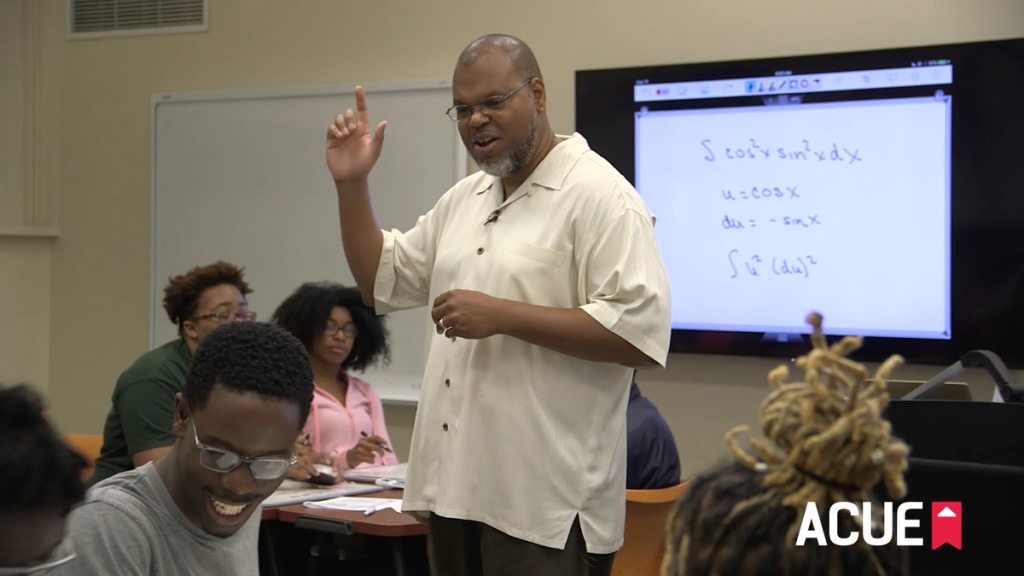

MM: There are obviously a number of things institutions need to be paying attention to, and not everything should be put aside in favor of teaching. But I think we have to recognize that, in far too many parts of American higher education, teaching has been assigned an extremely low priority. The main business that most college faculty are in is teaching undergraduates, and they get very little training in most cases for that work—they get evaluated in many institutions more on their scholarship than on their teaching, even if what they spend the most time on is their teaching. With very little support to enable faculty to do their jobs, something that comes through loud and clear is, “Folks, we really don’t care about teaching.” And that has to be addressed.

2. The report says, “Effective student/faculty interactions are correlated with increased retention and completion rates, better grades and standardized test scores, and higher career and graduate school aspirations.” Why do you think so many institutions leave faculty development out of their student success strategies despite the pressure they’re experiencing to raise completion rates?

MM: Well, I think one challenge is that our level of knowledge about how to improve teaching is not very high. It’s not surprising that that’s true because the subject has been so widely neglected. There are, of course, substantial exceptions to this generalization. But on the whole, attention has been given to assessing research performance in American higher education, with elaborate systems for measuring it. People measure what they care about, and they measure research, and they don’t measure teaching, except with student questionnaires, which are generally a weak indicator of performance.

3. So you think that designing some kind of framework for measurement would go a long way in disseminating the importance of teaching?

MM: I think it’s one thing that institutions should be investing in. And I want to be clear that I’m not simply talking about measuring teaching outcomes, but actually measuring, tracking, observing teaching performance. It’s very difficult to go straight from what a teacher does in class to what a student’s test scores are, because obviously those are influenced by a great deal of factors.

Actually, I think one of the things we’ve learned from a lot of work in K-12 is that conscientious observation of classrooms by trained observers with organized ways of providing feedback on performance can be very effective in improving teaching performance. When there are classroom observations in higher education—and again, there are exceptions—these observations are done, for example, by full professors going to the class of an assistant professor, but that full professor has not been educated about how to judge performance in the classroom. So those observations may actually be worse than nothing, because you’re getting random feedback.

4. What role can or should tenure evaluation and contract renewal play in elevating the importance of teacher quality?

MM: Experience from K-12 education suggests that there’s a real tension between doing evaluation for the sake of improvement and doing evaluation for the sake of promotion. And both are needed, but they should be kept in reasonably separate boxes. If you want to learn how to teach better, you don’t want to be putting on a show which is going to figure into whether or not you get tenure. So I think there does need to be a systematic way of assessing teaching performance and assessing teaching outcomes. But those ought to be complementary to attempts to learn more about how to improve teaching, by putting what’s learned into practice.

5. What can be done at the graduate level to help aspiring instructors reconceive of the role of a college faculty member, with attention to pedagogy and ongoing evaluation of their teaching?

MM: These are challenging matters. Graduate institutions are not, all by themselves, going to decide that they’re going to devote more of their energy to preparing future teachers. They’re only going to do that if the institutions make clear that they are looking for evidence of high-quality teaching. So really, it needs to start with the institutions leading activities that signal “we really care about this.” One of those is evaluation for promotion and tenure, how much weight is given to teaching and so on.

But an even more obvious thing is we simply can’t have teaching being done without thinking in a serious way about how to prepare faculty well and how to create environments in which they’re able to do good work. We have to change the concept of a teaching professional because, in the current understanding of undergraduate teaching, especially at four-year institutions, the PhD is a research degree, not a teaching degree. That’s not going to change unless the institutions signal that they’re going to value teaching and, similarly, if the institutions are willing to find the resources and determination to improve the working conditions of people who are in part-time positions or adjunct-type lecture positions. Without those changes, I think it’s going to be hard to make progress in any substantial way.

6. When you mention improvements for faculty in part-time or adjunct positions, what types of changes are you referring to?

MM: I think one is better job security. That doesn’t mean tenure, but it should mean multiple-year appointments, in many cases. A second is providing working conditions that allow people to do proper work. It’s really not optimal to have to meet your teacher for office hours at a Starbucks because your teacher doesn’t have an office. So relatively straightforward things like that are important. But something that’s subtler and may be even more important is if we recognize how valuable good teaching is and give the people who deliver the bulk of the teaching a voice in how the institution operates. Adjunct faculty, in some cases, are not even invited to faculty meetings, and they have very little opportunity to vote on matters that are going to affect them. That all reflects back and can be problematic.