Techniques to Help Underprepared Students Learn More

“Instruction is the core of any developmental education strategy,” Thomas Bailey and Shanna Smith Jaggars write in “When College Students Start Behind.” The report on underprepared students is the fifth installment of The Century Foundation’s ongoing College Completion Series.

Bailey, founding director of the Community College Research Center at Columbia University’s Teachers College, and Jaggars, director of Student Success Research for the Office of Distance Education and E-Learning at The Ohio State University, note that improving instruction is one of four key areas of reform for students coming to college less ready for the demands of the coursework than their peers. The authors support this assertion through an exploration of instructional programs that have produced promising results.

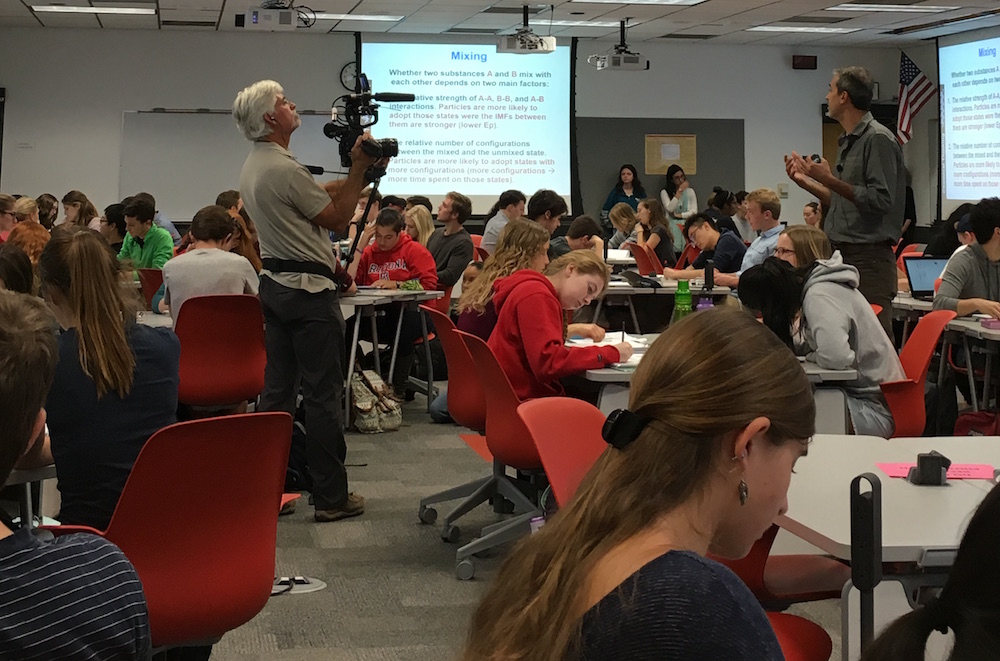

CUNY Start math classrooms, for instance, include real-world curricula that emphasize strong connections between coursework and students’ interests. Another example, the California Acceleration Project, encourages faculty to forge positive relationships with students and use class time for student-centered learning activities, among other techniques.

The report serves to prompt a broader discussion on how effective instruction can help underprepared students learn how to succeed in a college-level environment. To complement and build on the work of Bailey and Jaggars, ACUE’s teaching and learning experts present a list of specific research-based classroom techniques shown to help all students, and in particular underprepared students.

1. Use early, ungraded assignments to check students’ level of readiness.

Early in the term, an ungraded assignment can provide relevant information about your new students’ readiness and help you tweak your course plans. For example, ask students to write a few paragraphs on what they hope to learn in your class and give them a reading with accompanying questions. Or give a short quiz that measures math skills needed to begin work in your class (Gabriel, 2008).

2. Share exemplars of work products for your class.

Provide students with exemplars of papers, projects and presentations from prior years’ students. When possible, share examples that received a range of grades. Offering students exemplars to more clearly understand your expectations for an assignment makes it more likely that they will put in the time and effort required to meet those expectations (McGuire & McGuire, 2015).

3. Take time to learn about, and reflect on, your students’ goals.

Students not only enter college with differing kinds of knowledge and experience. They also enter with varying degrees of motivation to learn. Expert Linda Nilson explains the differences:

Bailey and Jaggars (2016) recommend tying course concepts to student interests, which any instructor can do. For example, you might use a one-minute paper exercise, asking students to answer questions like “What are your life goals and career aspirations?” and “How does this course help you pursue these goals—in ways big or small?”

Explicit connections between your course and your students’ future careers and aspirations are a particularly strong motivator (Nilson, 2010). Underprepared students are often unfamiliar with the skills that might be required in their future lives and careers, and showing them the relevance and significance of your subject will increase their motivation to learn about it.

4. Encourage student-to-student support

Early in the semester, bring in students from past years for a panel early in the semester to share what helped them be successful. You might ask questions such as these: How many hours each week did you spend studying and doing homework? How did you approach the readings? How did you prepare for exams? (S. D. Brookfield, personal communication, January 25, 2016). Hearing from a peer about what it takes to be successful can be more effective than the same message coming from the instructor.

5. Provide opportunities to use feedback to improve their performance.

Murphy and Destin (2016) call for “wise feedback” in Part Three of the College Completion Series. Dr. Thomas Angelo explains what exactly that means:

Offer specific and timely feedback—especially early in the term—so that students have the information and opportunity to make improvements. Having students rework an assignment— using your feedback to guide them— can be a valuable learning experience and provide the additional time and practice they need. This emphasizes the process of learning, promoting what Dweck (2006) calls a “growth mindset,” or the understanding that you learn more and become smarter through effort and practice.

Add to the conversation by adding your comment. What ideas and practices have you heard about or used that work?

References

Bailey, T., & Jaggars, S. S. (2016, June 2). When college students start behind (College Completion Series: Part Five). New York, NY: The Century Foundation. Retrieved from https://tcf.org/content/report/college-students-start-behind

Downing, S. (2011). On course. Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. How we can learn to fulfill our potential. New York, NY: Random House.

Gabriel, K. F. (2008). Teaching unprepared students: Strategies for promoting success and retention in higher education. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

McGuire, S. Y., & McGuire, S. (2015). Teach students how to learn: Strategies you can incorporate into any course to improve student metacognition, study skills, and motivation. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Murphy, M., & Destin, M. (2016, May 18). Promoting inclusion and identity safety to support college success(College Completion Series: Part Three). New York, NY: The Century Foundation. Retrieved from https://tcf.org/content/report/promoting-inclusion-identity-safety-support-college-success

Nilson, L. B. (2010). Teaching at its best (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.