4 Ways to Lecture Beyond the Bullet Points

By Mark Paternostro

Lecture déjà vu. I walked into a classroom in late September and realized I’ve given the same lecture, almost on the same date, in the same room for the past 10 years. I review my lectures every year and update content, but every so often we need to rethink lectures beyond the bullet points. Here are some ideas to help you think about lecture activities that engage students and promote learning inside and outside the classroom.

1. Grab your students’ attention.

It seems like an obvious idea, but we’re all guilty of starting off a lecture with “Today we are going to talk about…” and then jumping into the content. Showing short video clips or telling a quick story are good ways to get students focused on you and the day’s activities. For example, when I teach lung mechanics, I might start off with a video of Morgan Freeman talking on helium (yes, that video does exist!) or show a video of an elephant swimming and using his trunk as a snorkel. Students are engaged from the beginning, and this gives me an interesting way to introduce the main concepts.

Tip: Keep these activities to less than a minute.

2. Stop and take a breath.

Think about presenting material in small chunks. A 50-minute lecture can be thought of as three, 15-minute mini-lectures. Each mini-section should have its own beginning, middle, and end. You can then use the time between each session to engage students with some type of core learning activity. One simple exercise is a key word review. Present lists of key words and then give the students a minute to think about how the concepts are connected. Sometimes I will present a flowchart or short paragraph with blanks and have the students work in small groups to come up with the missing pieces. As they are working through the material, I interact with the small groups and then review the activity with the entire class.

Tip: It’s important to keep these in-class reviews simple. Students have just sat through 15 minutes of lecture and haven’t had time yet to synthesize or integrate the concepts into more complex ideas. Your goal is to make sure they understand the core concepts.

3. Create patterns.

In a nutshell, our brains are designed to recognize patterns. Pattern recognition helps us make connections, see things more clearly, and learn new things. In other words, things we would like our students to be able to do. We can take advantage of this by creating patterns in our lectures. If you use presentation software, look at the layout of your slides (titles, fonts, font size, image layout, etc.) and try to be consistent and regular. For example, when I teach physiology to first-year medical students, important concepts are bolded and words/phrases are color coded. All drugs are red, treatments are blue, and symptoms are green. Most students access the class material on laptops, but students who print black and white copies or who are color-blind can still see the patterns in the slide layout, bolded words, etc.

Tip: Your spoken words can create auditory patterns that reinforce the visual cues. Don’t read off the slides, but use the key words to drive the context of your discussion. As the students see and hear the words, pattern recognition learning kicks in.

4. Guide student learning.

I’m sure we have all thought it: My students don’t know how to study. I have often said this to myself, especially when thinking about my undergraduate courses. For many students, this class is the first time that they’ve had to go beyond the simple concepts of memorize and repeat. Students start my class thinking that making flashcards is the best way to study. I try to get them to understand that flashcards isolate content, and they might then miss the important relationships that are the basis of physiology. Instead, I try to get them to think about how clusters of slides are connected to one another and encourage them to integrate and condense information across related topics. To many, this is a vague concept. So, I provide examples of how I would study the material if I were a student in my class. I might condense content into tables or draw out neural pathways using boxes and color-coded arrows (pattern learning), adding details from the slides to connect the topics. Once they get the hang of it, they realize it is an efficient way to study complex material. Many have told me that they now use this application in other courses.

Tip: Encourage your students to handwrite notes/study materials. There are numerous studies that show the learning advantage of handwriting instead of typing notes. I tell students it’s fine to take notes in class electronically, but when they are studying outside of class, handwritten activities are more beneficial.

Even if you are comfortable in what you’re teaching, it’s a good exercise to think about how you are teaching. This is what makes teaching fun!

Mark Paternostro is a professor in the West Virginia University (WVU) School of Medicine and teaches human physiology for undergraduate, doctoral, dental, and medical students. He is featured in ACUE’s module Providing Clear Directions and Explanations.

Brighouse: Discussion Forums as Game-Changers

Mary-Ann Winkelmes: Teaching Expos as Engines for SOTL

Dr. Mary-Ann Winkelmes is nationally recognized as the founder of the Transparency in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education Project (TILT Higher Ed), which she shared with the ACUE Community in 2016. As a faculty developer, Winkelmes is also passionate about initiatives to promote teaching and learning on campus, including an annual Best Teaching Practices Expo that kicked off at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, in 2017. This month, Winkelmes started a new job as executive director of Brandeis University’s Center for Teaching and Learning, but she was still excited to talk to the ACUE Community in a Q&A about UNLV’s Expo and showcase her colleagues’ work.

What originally inspired you to organize a “Best Teaching Practices Expo,” and how has it evolved?

While UNLV has a tradition of excellence in scholarship and teaching, the UNLV Best Teaching Practices Expo in January 2017 was the first of its kind as a large, campus-wide event to call attention to scholarly, evidence-based approaches to teaching and learning at the institution. That first iteration was a poster exhibition, and we reached out to lots of faculty to recruit posters and generate interest in attending. This year’s event attracted many poster proposals, selected 34 posters, and drew hundreds of faculty who came to participate, talk with presenters, attend the panel presentations, and enjoy a buffet lunch together. The posters are published online on UNLV’s Best Teaching Practices site, making them widely accessible and easy for poster authors to cite in future publications or grant funding proposals.

The poster session is usually followed by panel sessions on shared themes like increasing students’ metacognition, engaging students across difference, and apps and tools to enhance learning. This year we added real-time voting by attendees, who used their cell phones or tablets to identify which practice they are most likely to adopt this term (The People’s Choice Award went to the poster on Dynamic Lightboard Videos for teaching online mathematics courses by Kristina Schmid, Peter McCandless, and Eddie Gomez).

What have you learned from the experience? What’s surprised you?

I had high expectations for this event, but I think even I was surprised by the large extent to which it is an engine for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning at UNLV. Some of these posters can lead to peer-reviewed publications and even external grants. For example, Jen Utz’s poster for increasing formative assessment and engagement during labs is related to her National Science Foundation grant, while Tiffany Howard’s poster from the 2018 Expo developed into a publication, “Transparency Teaching in the Virtual Classroom: Assessing the Opportunities and Challenges of Integrating Transparency Teaching Methods with Online Learning,” published in the Journal of Political Science Education.

What advice do you have for CTL directors or faculty developers who may want to bring similar events to their institution?

For colleagues undertaking a similar event, I’d suggest involving faculty, staff, and students in the organization, as we did. I’d also advise explicitly aligning the criteria for selection with the focus areas of the final posters and with the call for proposals. Our four criteria/focus areas were:

1. the practice and the significance of the need it addresses

2. evidence the practice benefits UNLV students

3. resources and where to find them (including state of research)

4. how other UNLV teachers might adopt this practice

This ensures the community sees the criteria multiple times, and they know that all posters will address these key points. This alignment gives some structure to a visitor’s experience when they visit the Expo, and it establishes criteria for excellence and even for voting during the event. An event like this is a great way to generate cross-campus conversations around evidence-based practices for improving teaching and learning experiences across the institution.

Behind the Poster

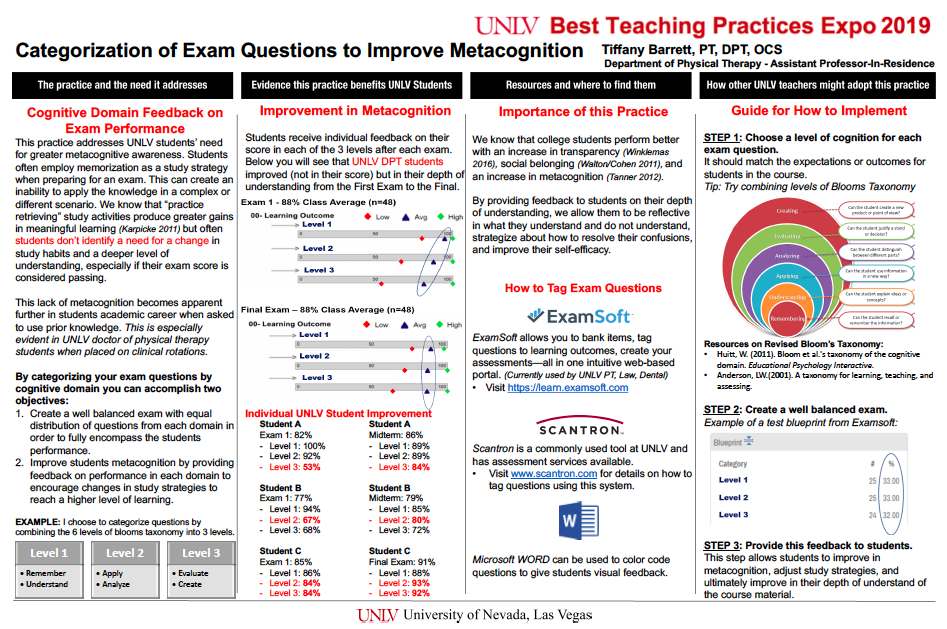

Dr. Tiffany Barrett, a Distinguished Contributor from the 2019 Best Teaching Practices Expo, shares a summary of her poster on the Categorization of Exam Questions to Improve Metacognition.

Students often employ memorization as a study strategy when preparing for an exam.

This can create an inability to apply the knowledge in a complex or different scenario. Students don’t often identify a need for a change in study habits and a deeper level of understanding, especially if their exam score is considered passing. By categorizing your exam questions by cognitive domain, you can accomplish two objectives: First, create a well-balanced exam with equal distribution of questions from each domain in order to fully encompass the  students’ performance. Secondly, improve students’ metacognition by providing feedback on performance in each domain to encourage changes in study strategies to reach a higher level of learning. UNLV students receive individual feedback on their score in each of the three cognitive levels after each exam. It was shown that students improved not in their score, but in their depth of understanding from the first exam to the final. By providing feedback to students on their depth of understanding, we allow them to be reflective in what they understand and do not understand, strategize about how to resolve their confusion, and improve their self-efficacy.

students’ performance. Secondly, improve students’ metacognition by providing feedback on performance in each domain to encourage changes in study strategies to reach a higher level of learning. UNLV students receive individual feedback on their score in each of the three cognitive levels after each exam. It was shown that students improved not in their score, but in their depth of understanding from the first exam to the final. By providing feedback to students on their depth of understanding, we allow them to be reflective in what they understand and do not understand, strategize about how to resolve their confusion, and improve their self-efficacy.

Dr. Tiffany Barrett is an assistant professor-in-residence at UNLV. She earned her Bachelor of Science in Nutritional Sciences from the University of Nevada, Reno and her Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) degree from the University of Colorado.

A Game-Changer in Accountability: Using Online Discussion Boards (Even in Face-to-Face Classes)

By Harry Brighouse

I often start my smaller classes with an icebreaker, mainly so the students start to learn each other’s names and are more ready to talk to each other. I recently asked, “Name a book you haven’t read that you think you ought to have read,” and one woman immediately said, “That would be all the novels from last semester’s English Literature class.”

It’s a familiar story. The lecturer isn’t confident that the students have read and understood the material well enough to talk about it. She delivers the content herself, so the students know that they will get everything they need from the lecturer without reading and will not be accountable in class for having done the reading. They can cram for the test from their notes, and a good essay prompt focuses students on particular reading which they might, reluctantly, have to do, but not while it’s being discussed in class. So, no reading.

At least that was the dynamic in my classes prior to the emergence of discussion boards. I eschewed a solution some of my colleagues use, which is a ‘pop quiz’ with simple, factual recall questions about the reading, because I didn’t want to signal that what I value is factual recall. I want students to learn how to think critically. But, even in smaller classes, I couldn’t trust that they had done the reading.

The game-changer has been the online discussion board.

My first lecture of the week is on a Tuesday, and most of the reading is assigned for that class. Thirty-six hours before class, the students must respond to a prompt about the reading—one that is impossible to respond to coherently without having done the reading. Settings allow you to prevent them from seeing other students’ responses until after they post. Then, they have until the beginning of class to respond to a classmate.

If students post, they get credit; if not, they don’t. Literally (and I mean that in the old-fashioned sense in which it actually meant “literally” rather than the modern sense in which it seems to mean “not literally”), if they submit a paragraph of nonsense, they’ll get credit. But they don’t. Their writing is public to me and their peers, and they don’t want to be embarrassed.

In smaller classes, the effect has been astonishing. Almost all my students do almost all the reading for almost every class. In my upper-level classes, the total word count for 20 students is often 15,000 or more. (Remember, one incoherent sentence would be sufficient for credit.) Some comments form the basis of papers; many are, themselves, rough (and, occasionally, not-so-rough) papers. The students feel accountable to me and one another. I know what they are thinking, what they understand, and what they don’t, which has transformed my preparation for class. It hasn’t made it easier or less time-consuming, but it has made it more interesting. Instead of guessing what might be useful to students, I can make well-informed judgments about what they need. I can talk much less in class than I used to, and my talk is more useful than it was.

In addition, they can each know what the others think before they come to class. In combination with a policy of making them learn each other’s names, it seems to make them much more engaged with one another. Students routinely refer in class discussions to ideas other people have posted online.

The board provokes the students to read more and makes the time in the classroom more focused on them. The fact that I know what they are thinking allows me to spend more time in class making them accountable for having done the reading—which they have actually done. Ironic, isn’t it?

Large lectures are different. I read many posts, and so do my TAs, but we don’t read everything. Typically students write a paragraph, and the response posts are often little more than a few sentences expressing agreement. I’m not a fool, and I don’t believe for a minute that all the students do all the reading. But I have evidence that many more do it than used to. (In particular, two of the readings should provoke outrage in many of the students, and, whereas before I adopted this policy, most students came to class on those days impassive, now many arrive in class steaming.) And, as with the small class, I have much better evidence than I ever had before of what they are thinking and what they do and do not understand, which enables me to prepare more relevant lectures and better prompts for in-class discussion.

This semester I’ve been personalizing the process for the large lecture more. I require students to sit by discussion section in the lecture hall, and the Canvas (LMS) settings make it easy to organize the online interactions by discussion section—so that each student interacts only with the posts of the other 20 students in their section (whose names they already know, after just a few weeks). Maybe this will prompt more reading and more elaborate discussions.

For a long time, I assumed that everybody else was doing this, partly because it is obvious and partly because, being basically a technophobe, I am usually 5 to 10 years behind everyone else for any given technological innovation. Some readers probably think it’s hardly worth mentioning. I’d agree if it weren’t for the fact that so many colleagues express surprise and curiosity when I describe it.

| What to read next: “Navigating the Need for Rigor and Engagement: How to Make Fruitful Class Discussions Happen,” by Harry Brighouse |

The Fullness of Our Humanity as Teacher and Student

Bringing your ‘A’ game to class discussions

Bring Your ‘A’ Game: Leveling Up Class Discussion by Incorporating a Sense of Play

By Traci Brimhall

I have been using a Jeopardy-style review game for midterms almost as long as I’ve been teaching. Those review days always go well. Students invest in the competitive aspect, and the categories of Jeopardy allow me to review key concepts and our stated learning objectives. Jeopardy’s format (in which others can steal an answer) keeps all members of class actively engaged in every question. Since students seem more invested on days that involve a game, I have started to incorporate more elements of play into class research, discussions, and engagement triggers. I describe some of these below.

I have been using a Jeopardy-style review game for midterms almost as long as I’ve been teaching. Those review days always go well. Students invest in the competitive aspect, and the categories of Jeopardy allow me to review key concepts and our stated learning objectives. Jeopardy’s format (in which others can steal an answer) keeps all members of class actively engaged in every question. Since students seem more invested on days that involve a game, I have started to incorporate more elements of play into class research, discussions, and engagement triggers. I describe some of these below.

Bingo

Rules of the Game. When covering a subject that has a lot of terms and/or history, I play Bingo. I make five different Bingo sheets with the same terms scrambled in different places. Students draw several terms from a box and then have time to research those items. When we are ready to play the game, I collect the slips of paper with the terms on them and then draw those items at random. Whoever had that term during the research time then explains that concept to the class. I follow up with any other important key points, and then I draw out the B-I-N-G or O and instruct anyone with that term in the selected column to cross it off.

How Everyone Wins. The game aspect of this activity keeps everyone engaged and following the information. The research aspect makes students take charge of their learning and figure out where to look for answers. It also encourages them to see that if they have a question while reading, they can seek out more information. By sharing that information when their term is called, they are also furthering their learning by rephrasing it and trying to teach others the new knowledge they’re acquiring. Since it’s an activity that incorporates the whole class, I also have the chance to listen and assess how their independent research went and make sure to fill in any gaps that their explanation left out so the students don’t have incomplete or incorrect information.

Celebrity Heads

Rules of the Game. This classic parlor game adapts well to humanities classes. Rather than assign each participant a celebrity, I assign students characters from a novel/story or one of the writers we have discussed in the class. (I do this with Post-it notes on their backs.) Students can’t ask leading questions, and every question must have more than one correct answer. They are also limited to two “yes or no” questions from one person, and then they must move on and ask others.

How Everyone Wins. The rules for asking multiple classmates questions allows for some good one-on-one time for peers to interact and create community in class, but it’s also a great activity for critical thinking. Students must think about what characters or writers have in common or what sets them apart so they can ask good questions that will help them narrow down who the character or writer might be. After some discussion time, they make a guess about their identity and are asked to find a passage from the text that best represents them. Since I assign more than one person the same identity, I then have them find their match and discuss their questions, quotes, and thoughts about that character/author before we review and discuss as a class.

Musical Chairs

Rules of the Game. This one is an adaptation from my time in ACUE! I’m a teacher who struggles with silence. I do a fair bit to make sure my students are prepared to discuss, such as think-pair-share and a short writing time so students have time to process their answers to questions. However, when one of ACUE’s learning modules prompted instructors to sit in the silence until students were prepared to answer, I turned that into a game of musical chairs. Every question I asked was an opinion statement, so as to not put the students in a right/wrong situation where they would fear to answer. In each round, three chairs were taken away so that when the music stopped playing, those three people would share their answers and briefly discuss with each other. They were then allowed to sit down, three more chairs would be removed, and I would ask a subjective question and play more music as students circled and considered their responses.

How Everyone Wins. The music gives students a chance to process their thoughts and also lets me make a connection with them. I often choose a certain song and say why I love it. It could also easily be connected to course content. This activity makes students get up and move around, which has been something my morning class requested that we do more of.

Cards Against the Humanities

Rules of the Game. I split up the class into groups and give each group a critical thinking question. These function as the black cards in a traditional Cards Against Humanity game. A group asks the question and the other groups discuss and write their answers on index cards that remain anonymous. The index cards are then submitted to the group who asked the question, and they determine the best critical thinking response.

How Everyone Wins. This activity keeps everyone engaged in crafting critical thinking responses and evaluating critical thought for strength of argument and/or uniqueness of approach.

Many of these techniques are just the game versions of lesson plans I already do—critical thinking questions, subjective engagement triggers, midterm review—but by adding in the element of play, students seem to invest more, and it keeps a more uniform sense of engagement across the class.

Traci Brimhall is the author of three collections of poetry. She’s an associate professor at Kansas State University and teaches creative writing, literature, and medical humanities.

Faculty make institutional transformation possible

Navigating the Need for Rigor and Engagement: How to Make Fruitful Class Discussions Happen

By Harry Brighouse

Derek Bok’s great book Our Underachieving Colleges contains a passage that, ultimately, transformed my teaching.

Derek Bok’s great book Our Underachieving Colleges contains a passage that, ultimately, transformed my teaching.

Teaching by discussion can also seem forbidding because it makes instructors uncomfortably aware of their shortcomings. Lecturers can delude themselves that their courses are going well, but discussion leaders know when their teaching is failing to rouse the students’ interest by the indifferent quality of responses and the general torpor of the class. Trying to conduct a discussion with apathetic students is much like giving a bad dinner party.

Reading it was like receiving a slap in the face from someone who had been sitting in my classroom, and knew me better than I know myself.

Why do we lecture so much? All teachers experience a tension between the need for engagement and the need for rigor. Without rigor, the students won’t learn what we want them to; without engagement, they won’t learn anything at all. In the classroom, the best way to guarantee rigor is for the professor to do all the talking—this is how they delude themselves that the class is going well. Unfortunately, this is also the best way to ensure complete disengagement, leading to torpor when we do try to stimulate discussion.

Students have to talk and write, because talking and writing are essential for practicing the discursive practices and thinking skills that we are trying to make them learn in the humanities. We can make them write (some) outside the classroom; but in my experience most students have to talk in the classroom if they are going to talk at all.

Realizing that students need to discuss is helpful, but actually knowing how to make them discuss is another matter—it’s a skill that has to be learned. The challenge is not getting them to talk, but doing so without sacrificing too much rigor—how to ensure high-quality thinking and talking which engages the whole class.

Over time, through reading, observing excellent discussion leaders, and practicing what I’ve learned, I’ve become reasonably good at making inclusive and productive—and often rigorous—discussions happen in my smaller classes (of 15 to 25 students), and have even been able to inject some fruitful discussion into each session of my larger lectures.

Like other professors, I know my own discipline, not others. I’m reasonably successful at prompting and managing on-topic rigorous discussions about philosophy. But I don’t know how to discuss a movie, or a novel, or a history book. What follows, then, are some strategies that work for me, with my students, in my classes.

Here are some rules of thumb for smaller classes:

A discussion is not 20 individual dialogues between the professor and 20 individual students. It is a discussion like the discussions you are used to having in meetings and research seminars. Everyone is addressing the whole room. Students find this very difficult at first. So do I.

My students are inclined to deference, and tend to want to look at me, and speak to me, even though I specifically tell them to talk to the whole room. If they’re looking at me too much, I tell them to look at other people (gently, kindly). A less disruptive strategy is to casually walk around the room and regularly stand behind whoever is speaking so that they pretty much have to look at other students.

My dad has been telling me for years that “You’ve got to work on your questions.” What he means is that fruitful discussion depends on the right prompt. TV talk show hosts know which questions will draw out their guests; we need to know the right questions to draw out our students. The ideal discussion prompt is not factual recall or “What do you think?” but a question to which there are different and conflicting reasonable answers, and about which you have good reason to expect different students will respond differently.

A colleague with 40 years of teaching experience told me that he had always struggled to make discussions happen in class until, recently, he observed his TA running a discussion section. She used “think-pair-share” and, he said, “It’s like magic!” It really is, if you have the right prompt. Simply ask students to talk in pairs for a couple of minutes before they discuss things in class. Students have something to say and feel less like they’re being put on the spot, because “We said that…” is less committal and opens up space more than “I think that…”

Most teachers understand that they need to know the names of all the students. Less obvious is that the students need to know each other’s names. If you are trying to get them to discuss with each other, it is easier for them to do that if they know each other. This is especially true if the issues in the class are ones about which they are liable to disagree, and about which they feel passionately.

In discussions of hot button issues, like the morality of abortion, students are very sensitive to how they will be judged by their peers. Assuring students that we are exploring the space of reasons, and that we are thinking—carefully and precisely—out loud, seems to help them feel that they will not be judged and, actually, will not judge each other. The better they come to know each other, the less assurance they need, because the more trust they have built up.

Cold calling is like anything else. If you don’t know how to do it, it won’t work. If you do, it will. For cold calling to work, the question must be good, you should look the student in the eye and use their name, and you should assure students, ahead of time, that if they have nothing to say it really is okay for them to tell you that.

Some of these strategies work in large lecture classes too. Small-group discussions and think-pair-share have to be briefer than in smaller classes, because students go off topic sooner and are harder to monitor. I can’t learn all their names as quickly (or, in very large classes, ever), so I am much more cautious with cold calling. The more students in the room, the harder it is to keep them all engaged in a whole-class discussion in which most of them know they won’t speak. It’s much more work to ensure widespread participation. Remember that a discussion in which three people do all the talking is not a discussion but a series of soliloquies to which nobody listens. But the basic principles—design good prompts, make the students address the whole room, and assure students that we are all engaged in the same activity—seem to work across formats.

I still sometimes find it extremely difficult to resist talking too much myself. I have fostered a gestalt switch in my head, so that when I find myself thinking “I’ll be depriving them of my brilliance, and the truth, if I don’t correct them,” I prompt the thought “Ah, but if I correct them, I’ll be depriving them of the experience of thinking things through themselves.” I still talk more than I should. But things are moving in the right direction.

| What to read next: Four Ways to Spark Engaging Classroom Discussions |

Reference

Bok, D. (2006). Our underachieving colleges: A candid look at how much students learn and why they should be learning more. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.