By Ken O’Donnell and Natasha Jankowski

The circa 2000 professor had responsibility for a narrow slice of the university’s life, connected to a specific discipline, students in the major, and a limited number of service obligations. Unless you were in the academic senate or involved in accreditation, there was little expectation of an institution-wide view or thought to how pieces may or may not fit together.

Several related pressures are changing that, and adding integration and a systems view to the responsibility of front-line educators—whether student affairs professionals, tenured/tenure-track faculty, or lecturers. The shift entails a greater expectation to situate work intelligently and intentionally in the rest of the institution’s mission—to be an interconnected part of something larger. A rundown of the sources moving this shift along include:

Student Success: Our colleges are held to higher standards for graduation rates and genuine equity—not merely admitting students of all backgrounds, but also seeing them through to completion. Those with off-campus jobs are often the hardest to help, experiencing the campus mostly as a classroom and parking lot. Every interaction with them, however fleeting, has to count.

Interdisciplinarity: Research, scholarship, and creative activity are likelier to cross department lines, as the world gets more connected and this century’s most urgent problems—for example, in social justice, global trade, climate change, and cybersecurity —demand changes not only in technology but also in culture. Solutions won’t come from one field at a time, and research agendas confined to a single department or college are getting harder to justify and fund.

Big Data: These days, the exciting ideas at higher education conferences are at the vendor tables near registration. Each software platform promises to show me, on my phone, how my students are doing—in terms of the demonstrated learning in their ePortfolios, their progress to degree, their graduation rates in my home chemistry department versus those at like institutions, their Pell-eligible retention relative to a propensity-score-matched control group. These tools are potentially game-changing, but only if we all know what we’re looking at.

These three pressures intertwine and work together: As our students spend less time on campus, and we are each presented with more information about how they’re doing and how we can help, more and more functions of the university seem contained in each of us, the newly fractal educator.

So, what do we do?

How is the responsible idealist to focus on the learning of an individual student, while also embodying the mission statement, and containing multitudes?

It may not come as a surprise if you know the authors, but we are pretty sure the answer lies in valid assessments of high-impact practices (HIPs). Hear us out.

HIPs literature in its first decade has emphasized the power of certain experiences in college— like learning communities, undergraduate research, and service learning—to deepen learning while improving persistence for all students, especially the traditionally underserved.

In other words, they satisfy much of the completion-with-equity-and-quality agenda, and they do it with parsimony. A single well-designed and well-executed high-impact practice can maximize our interaction with students, even those who commute.

The challenge, of course, is defining “well-designed” and “well-executed.” How do we know if these HIPs are any good? Well, the answer is probably less in detailed accounts of what students will do, and more in the demonstrated learning that results.

For example, we know the world and its employers need more team players and fewer soloists, and are putting a new premium on interpersonal skills as an attainment of college. Service learning and civic engagement seem to develop those, but the specific activity is less important than the proof it worked.

Here are four things educators can do right now to make sure their high-impact practices really are high impact:

1. Design HIPs that develop multiple proficiencies in complicated settings. Use the NILOA assignment design library or assignment charrette process. Go for outcomes beyond content knowledge, using the LEAP Essential Learning Outcomes, the NACE career-readiness proficiencies, and other frameworks to ensure the learning is comprehensive, applied, and relevant. HIPs provide us an opportunity to support the integration of transferable learning with our students. Let’s not let it pass us by.

1. Design HIPs that develop multiple proficiencies in complicated settings. Use the NILOA assignment design library or assignment charrette process. Go for outcomes beyond content knowledge, using the LEAP Essential Learning Outcomes, the NACE career-readiness proficiencies, and other frameworks to ensure the learning is comprehensive, applied, and relevant. HIPs provide us an opportunity to support the integration of transferable learning with our students. Let’s not let it pass us by.

2. Tell your students why you are asking them to do the things you are and how they connect to something larger. Use findings of the UNLV transparency project to inform the way you tell students what they should get from the experience. Make their learning visible, metacognitive, and intentional.

3. Make your students do an ePortfolio, even if you’re the only one in your whole state. (We can connect them later.) What’s important is that the portfolio capture before-and-after evidence of each of the disparate learning outcomes in your HIP. So if their environmental impact presentation for a local nonprofit is meant to develop critical thinking, quantitative reasoning, written expression, and oral communication, then make sure each one of those outcomes is developed and documented, and that the student can explain how—for example, during a job fair or elevator pitch—concisely and confidently.

4. Connect your work to others. Use the NILOA toolkit as a way to talk to your colleagues about exactly where students are attaining each proficiency during their time with you and where it may have been reinforced or developed that has been missed. These can be in traditional courses or other experiences, not as additional things to add on, but ways to integrate and reinforce, because the more of our students’ week we claim, the fewer opportunities they have for everything else. Use the work of the Comprehensive Learner Record (CLR) and other tools to locate specific learning within the context of the whole degree—visualizing for students and others the integrative nature of the collective impact of an institution that comes together around their students.

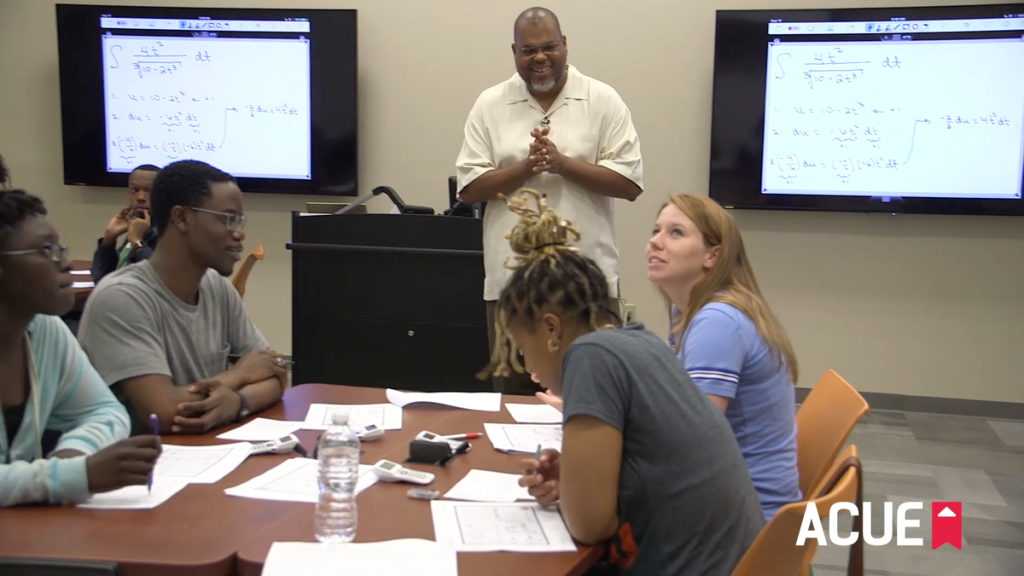

Join online communities of practice, such as NASH’s Taking Student Success to Scale, the professional development tools available through ACUE and others, and AAC&U, AACRAO, and NASPA to ensure that the visible learning of your students will be intelligible to others in the business of educating them. Much as we are not alone within our institutions in educating our students, we are not alone in higher education as we try to address our shared difficulties.

These four things aren’t easy; they require a new conception of our individual contributions to the enterprise, and really of higher education itself. They entail a new commitment to professionalizing the profession, as we try to live up to our newly expanded roles in the academy.

But this feels to us like the kind of hard work that’s worth doing. The problems of the 21st century are daunting, and addressing them will require a population more fully and demonstrably educated than ever before. We’re ready to dive in. Will you join us?

What to read next: Person, Place, or Thing? Implementing High-Impact Practices with Fidelity