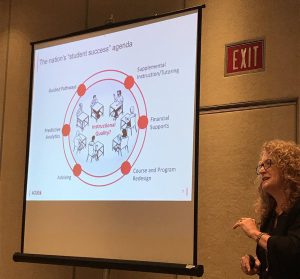

Change is never easy, so it’s natural for educators to feel some reluctance about implementing a new teaching practice. “It requires a willingness to take risks, careful planning, and a commitment to student learning,” explains Christine Harrington, executive director of the New Jersey Center for Student Success.

Just as important, Harrington adds, is that faculty know the research behind the practice so that they can give students the rationale for why they’re using a particular approach. “It adds credibility to what you’re doing in the classroom.”

Harrington spoke to ACUE during last month’s Lilly Conference in Bethesda, Maryland, where she was a plenary speaker. A recognized expert and writer, Harrington is author of Student Success in College: Doing What Works! and has also coauthored with Todd Zakrajsek Dynamic Lecturing: Research-Based Strategies to Enhance Lecture Effectiveness. In this interview, Harrington shares advice for how faculty can collaborate with both colleagues and their own students to effectively implement evidence-based practices.

Why did you begin using research-based student success practices?

When I first started teaching, I taught based on what I knew. I took what I like to call an advice-based approach. Many faculty are mostly communicating what they did as students and what worked for them, or they’re pulling from what their friends and family have experienced.

When you look at the research behind teaching practices, a couple things happen: First, it gives credibility to what you’re doing in the classroom, especially when you give students the rationale for why you’re using this approach. Second, it works. It’s more effective.

For example, while attending a student success workshop, one of the presenters said, “When you’re giving a test, take students’ pencils and rip the erasers off, so they can’t change their answers.” When I looked at the literature, there was no research backing up that statement. It says exactly the opposite: Research by DiMilia (2007) and Shatz & Best (1987) shows that you’re more likely to change your answer from wrong to right than from right to wrong.

So sometimes we’re actually giving incorrect information to students or using approaches that are not necessarily effective. By reviewing the research, you can feel more confident in the approaches you’re using.

What advice do you give faculty who want to implement research-based methods that are new to them—but are hesitant to do so?

We have to model risk-taking in the classroom. We ask our students to take risks all the time, and we have a lot more confidence than they do, because we’ve been teaching for a long time. Change can be challenging. We have to push ourselves.

The first step may be to work with your teaching and learning center, if you have one on your campus, so you can intentionally talk through how to best integrate a teaching strategy.

They can sit down with you, help you plan, determine the best conditions for the strategy, how to set it up, and what you need to do to prep the students for it. For example, I once had a colleague try a think-pair-share activity after attending one of my workshops. She came back and said, “I went in, I tried it, and it didn’t work.” I asked to hear a little more about what she did. My colleague said she tried it for the first time mid-semester, and all of the sudden said, “Turn and talk.” Students didn’t know what to do, because she didn’t set the stage.

I would also encourage faculty members to work with other colleagues to observe and give each other feedback in a non-evaluative and collegial way. That can be really powerful, especially when trying something new.

In addition to getting feedback from colleagues, how do you involve students when you’re trying something new? How do you check to make sure the learning you intend is taking place?

Reflection is a great activity that can often demonstrate that students are really learning—but it needs to be a cognitive task for students. You want to make sure that students are prepared to reflect, you’ve prepped them, and you’re not just saying, “Go be metacognitive. Good luck with that.”

I sometimes say to students, “We’re going to try a new strategy. Here’s what it is. And I’m going to ask you for your feedback on whether it works or not.” Sometimes the initial feedback is, “This feels uncomfortable. I’d rather just sit here and listen.” But then they reflect on it and discover that it was pretty powerful.

You want to structure the questions and scaffold them along the way. You want to help students see how their own reflection on a topic promotes deeper learning. And you want to share with your students the rationale on why they are doing the activity, whether in writing or verbally in groups, so they know it’s not “busy work.” I often share actual research on the topics I’m talking about so students can understand why this is so important. I want students to know that I’m not asking them to write for the sake of writing, but that the type of writing I am assigning leads to increased learning.

What do you tell faculty who say their primary responsibility is to deliver content and that they shouldn’t be concerned with researching teaching practices or teaching student success strategies?

I ask, “How successful have you been with that?” If your strategies are working, then great. But if students aren’t mastering the content, then that is an indicator that you need do something differently.

Using effective pedagogical practices can help increase student learning. Expertise in the discipline and in teaching approaches both matter. One interesting study conducted by Ruhl, Hughes, and Schloss (1987) shows how teaching less can increase learning. In this study, the instructor does not talk for six minutes of the class period and instead asks students to share and compare their notes during three two-minute pauses. Results indicated that this approach led to increased learning because the pauses give students time to process. Helping faculty see the research behind these teaching practices has a major impact.

What teaching practices do you use to empower students who don’t feel capable of learning—or mastering—the content in your course or discipline?

My favorite answer to that question comes from Carol Dweck, who talks about the power of “yet.” When students say, “I can’t do that,” you say, “You mean, you can’t do that yet.”

Think about the hope that instills, to say to the student, “You’re saying you can’t do math now, today, at this moment. All right. But if you’re saying you can’t do math ever? Sorry, not buying it. That’s why you are here—to learn.”

I tell students there are a lot of other people who have said the same thing and discovered they could do it. We can instill hope by sharing our own stories and the success stories of others who are like them. I even put them on the hunt to go find these stories. I say, “I want you to go find someone else who felt the same way you do right now and passed the math class. Maybe even majored in math? Or uses math regularly?” It’s amazing how easy it is to find those folks, and how willing these people are to share their experiences. These stories are so powerful.

What are some of the ways that you and your colleagues have communicated to students the research basis of your teaching methods? Share your stories and insights in the comments section!